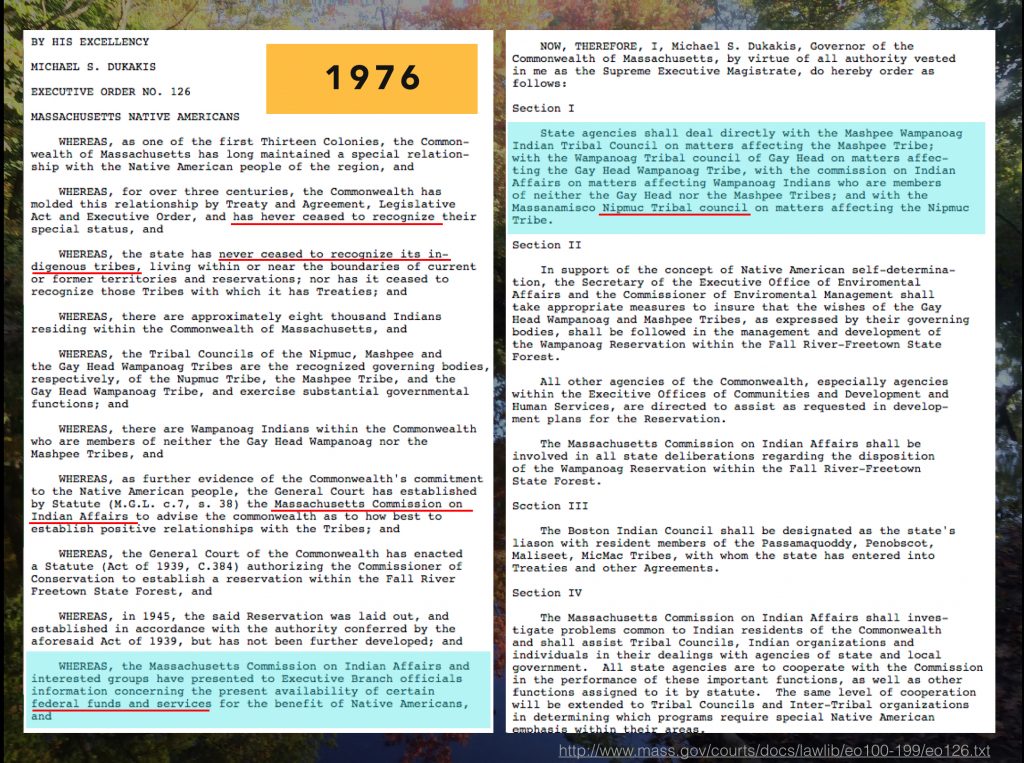

WHEREAS the state has never ceased to recognize its indigenous tribes…. WHEREAS, there Tribal Councils of the Nipmuc, Mashpee and the Gay Head Wampanoag Tribes are the recognized governing bodies… The Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs shall investigate problems common to the Indian residents of the Commonwealth and shall assist Tribal Councils, Indian organizations and individuals in their dealings with agencies of the state and local government.

Executive Order no. 126, Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts (1976), my emphasis

As the Sami elected body in Norway, the Sami Parliament’s goal is to promote recognition of the Sami’s fundamental rights as a basis for safeguarding and strengthening Sami culture, language and social life and the existence of various Sami traditions.

“Rights”, Sametinget.no (2018), my translation, my emphasis

For many indigenous peoples, “being recognized” has come to mean not simply being known and acknowledged by one’s own relations but also being seen in the right way by the eye of authority. From the 1970s to today, new governance strategies focused on recognition have emerged in many nation-states with an indigenous population. In order to gain access to the resources, rights, and legitimacy that state recognition confers, indigenous political actors must both raise public awareness and navigate bureaucratic processes ranging from court proceedings to paperwork petitions. Though these processes purport to deliver factual determinations, they are in fact richly performative, actively generating the very social categories that they profess to evaluate.

The initial idea for this particular research project has roots in my first visit to the Centre for Sami Studies at UiT The Arctic University of Norway several years ago.

I was just beginning my PhD program at UMass, and had just finished a Masters degree that focused on a transboundary context along the U.S.-Canada border (see the trailer for this film project on my Vimeo page). At the outset, I knew that Sápmi (the traditional territory of the Sami) spanned four modern nation states, and I was wanted learn more about the history of differences in rights and histories across those borders. But when I arrived in Tromsø, I was struck by all of the developments in Norway in particular since the 1970s. The mechanisms and results of state recognition here in Norway were radically different from what I was familiar with from my previous work in North America. Around the time that returned to the U.S., I read Kim TallBear’s insight that sometimes producing better knowledge “requires shifting one’s feet” (Native American DNA, p. 24), and it clicked into place that there was something I could contribute by studying the conditions of indigeneity in Norway and at home.

I worked with my dissertation committee chair at UMass, Dr. Sonya Atalay, to see if there was a way that my dissertation project could become an opportunity to learn more (and more deeply) about indigenous history and contemporary challenges in southern New England, where I had grown up and later returned for graduate school. I began learning about the history of Nipmuc engagements with state and federal routes for official recognition of indigenous people, and with the help of Dr. Rae Gould, UMass Amherst University Tribal Liaison, I reached out to the Tribal Council of Nipmuc Nation to seek their approval of the project and open the way to conducting interviews with tribal members. After a year working on the Nipmuc case and followed by six months in Oslo in 2018 learning Norwegian and working to better understand the Norwegian political context for Sami issues (supported by GROW and the Social Anthropology Institute at the University of Oslo), I am now back at the Centre for Sami Studies where the seeds for this work were planted three years ago and where comparative consideration of indigeneity is a central topic of scholarly inquiry.

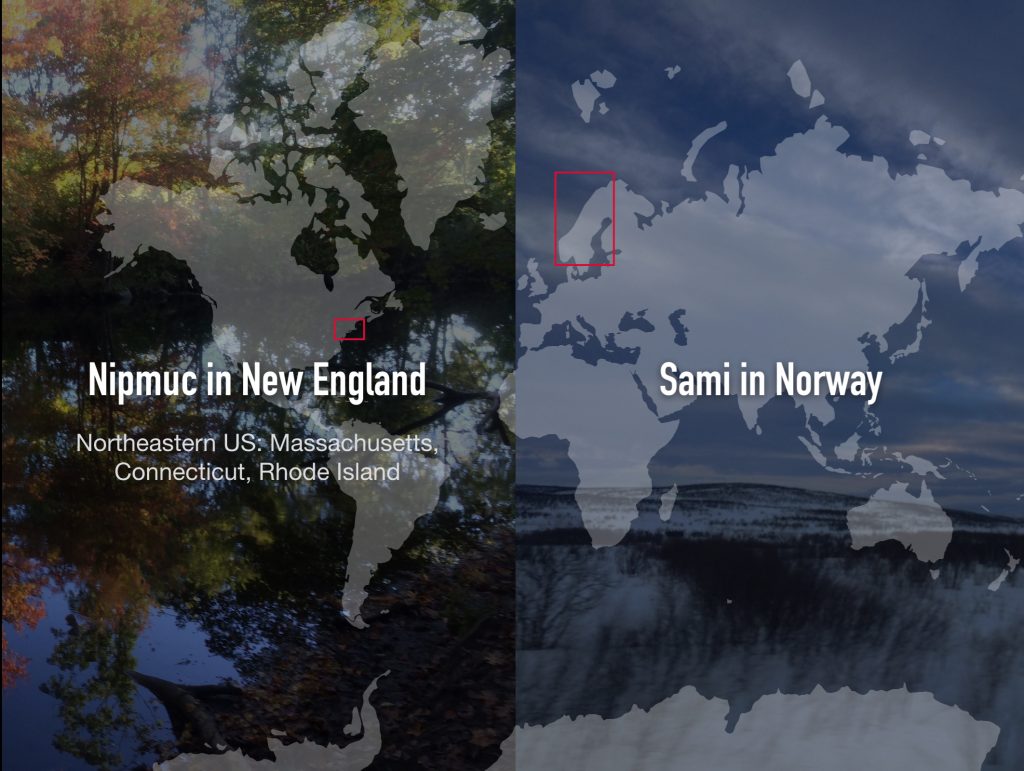

In my dissertation research, I am examining two simultaneous—but quite different—stories of indigenous peoples’ experience with state recognition. The first is in the region of the U.S. I am from and where my home university is located: a group of small states in the northeast, often called southern New England. This area is not often centered in national or international discussions of Native American politics, but, in fact, a full third of all modern land claims settlements since the 1970s have taken place in New England, and tribes and communities are still very active today.

My research follows, in particular, the journey of Nipmuc people as they navigated the federal recognition administrative process of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This process requires tribes to document the way in which the tribe and its members fulfill seven criteria. Nipmuc leaders formally began this process in 1980 and work was ongoing until 2018, when the most recent appeal of the BIA’s negative determination was denied in federal court. This kind of case—and Nipmuc Nation is not alone; other tribes, too, have engaged with the recognition process without achieving federally recognized status—are rarely the focus in international discourse about indigenous peoples and indigenous rights.

The second group is the Sami, specifically the Sami in Norway, a history I was able to begin learning in the first place because it is better represented in the international sphere. Though the processes stretched over the same span of decades, the Sami experience with the Norwegian state have been quite different than the Nipmuc experiences with state and federal governments in the U.S. One of the key points I have identified for comparison is the context for the formulation of the specific criteria used by the state to implement recognition. In the U.S., those are the seven criteria used by the BIA. In Norway, the only criteria one will find are the enrollment requirements an individual must meet in order to vote for representation in the Sami Parliament, created in 1987, through the Sami Act. These criteria were proposed in a 1984 public report, NOU 1984:18 Om Samenes Rettstilling, the first report of the Sami Rights Committee, named in 1980, during a time of much activism and public debate around the central government’s plans to build a hydroelectric dam in a Sami area in the northern reaches of Norway.

During my current period as a visiting researcher at the Centre for Sami Studies, I am focusing on the history leading up to the establishment of the Sami Parliament and the criteria for enrollment to vote in elections to the body. Part of my thesis will be an examination of how the development of these criteria in Norway differ from the establishment of the seven criteria used by the Office of Federal Acknowledgement in the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. But a driving method in my approach is also to hear from people who were engaged with these developments personally about how they experienced the process. Was this pursuing and helping to shape what recognition of indigenous peoples will mean an empowering process?

Did it change the way that people thought about their identity and their relationship to the nation state? To this end, I’ve already conducted a series of interviews in the U.S. regarding the Nipmuc history, and I am in the midst of conducting similar interviews while I am in Norway January to August of 2019.

What does it mean that it is so common to use the term recognition—often in English—in internal discussions about indigenous peoples and their rights? Even though we use a common concept, we’re often describing goals, events, and processes that differ substantially from one another. How can researchers study these differences in a way that makes them visible and understandable not only in international scholarly discussions but also for those who live and work within indigenous communities? How could this kind of work improve our understanding of the diversity of experiences of the peoples we call ‘indigenous’? One of the big contributions of the global dialog between indigenous peoples since the 1970s has been to open up minds in just this way. I hope my project, too, can be fruitful in building that kind of knowledge.

References

TallBear, Kimberly. 2013. Native American DNA : Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

This research is supported by NSF #IIA-1261172, NSF GRFP #1451512, the Norwegian Research Council, UMass Amherst Graduate School Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, and UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Vil du lese om dette prosjektet på norsk? Den norske versjonen av teksten ovenfor er tilgjengelig på Forskning.no.